This isn’t a cry for help or call for attention or confidence boost or an attempt for some sympathy. This is a genuine question I am grappling with as a local artist who already works in Woolwich, but who seeks to work in a more meaningful, empathetic and responsive way in my practice, in and with my local community.

In 2010, Lucy Lippard an American writer, art critic, activist and curator asked…

Is the artist wanted there and by whom? Every artist (and anthropologist) should be required to answer this question in depth before launching what threatens to be intrusive or invasive projects (often called ‘interventions’)

(Lippard 2010: 32)

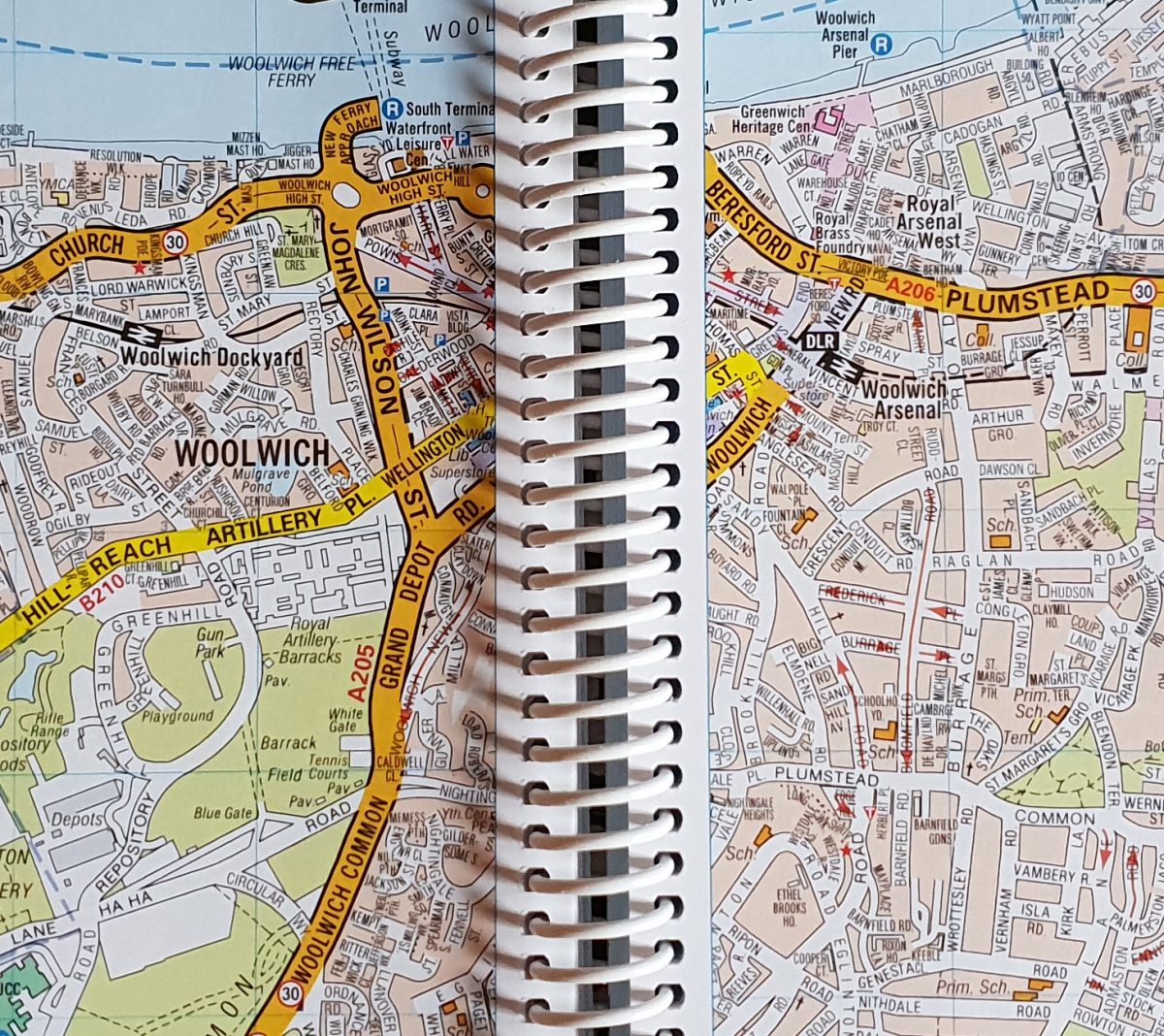

I asked myself this before writing my PhD proposal. I didn’t know the answer then and so was very mindful of creating a concept for an artistic project that enabled me to be projective and not prescriptive. This led to thinking about my own experience in this neighbourhood as a resident and how much I didn’t know about the place and the people. I quickly progressed to feeling a sense of outsiderness, of being a tourist (although I didn’t have a guidebook or tour to follow) and took this gaze with me on my walks. Each walk felt like an expedition, a discovery of: the physical spaces – the streets, the dead ends, the green spaces, the alley ways, the shops, the market places, the civic spaces, the Military land and buildings, the barriers, the open gates, the building sites, the transport links, the road crossings, the stairwells, the underpasses, the river, the common fly tipping sites, the houses, the driveways, the front gardens; and the people that bring meaning to these spaces.

This sense of being an outsider, of being on the back foot, as a newbie in Woolwich was humbling and I hope, respectful. It was also sponge-like…absorbing the place with every walk, and every pause and every encounter with others. Some encounters were fleeting, others involved a brief conversation, and one led to an invitation to lead dance classes with a group of Vietnamese women on Thursday mornings at Woolwich Common Community Centre from May to October 2019, just before I took maternity leave for a year.

And so to thinking about where I am now with this project. In January I begin a process of getting to know the people of Woolwich better through what is described as creative ethnographic research tools: photo journals, photo elicited interviews and walking conversations. I hope to gently find out a little more about their everyday lives, the places that matter to them, and their experience of Woolwich in is current transitional state.

This way of working as ‘artist as ethnographer’ is not new. Its described by art critic and historian Hal Foster (1995) as the ethnographic turn in contemporary art in the 1990s. In their introductory article to the issue of Critical Arts (Issue 5, 2013), Kris Rutten, An van. Dienderen and Ronald Soetaert summarise this approach as blurring the boundaries of the fields of art and anthropology, leading to a third space or borderland that crosses disciplines. Where “art projects are presented as (a kind of) ethnographic research and ethnographic research is presented as (a kind of) art. ” (Rutten et al 2013, pp460-461)

I am clear that I am not producing an ethnography of Woolwich. I will not be speaking ‘about’ or ‘for’ the Woolwich residents who choose to take part in the research. The photo journals and walking conversations provide a creative place for residents reflect on what it means to live here. The relationship between artist and subject will always be unequal no matter how much you work at providing an inclusive and accessible way into participation. And so, it is important to foreground this inequity and try to instead do what film maker, writer and composer Trinh Minh-Ha suggests, to speak ‘nearby’. Should participants consent to sharing their contributions in a collective exhibition of sorts, I will facilitate this…which also requires me to grapple with the messiness of co-authorship and attribution. Ultimately, I seek to benefit from this project since it forms part of my PhD, for which I receive a scholarship. Participants in this research are volunteers with expenses covered. And so the ethics of this work are ever present and challenging and I wrestle with solving these issues so that the project does not become intrusive or invasive, as Lippard warns, or for that matter, unethical.

So to answer Lippard’s question, “Am I wanted here and by whom?” I guess I will find out next year.

The completion of this phase of the research in 2021 will mark a significant pause and moment of reflection before planning what will and won’t come next.

References

Lippard, L. (2010) Farther afield. In Between art and anthropology, contemporary ethnographic practice, ed. A. Schneider and C. Wright, Oxford and New York: Berg.

Kris Rutten, An van. Dienderen & Ronald Soetaert (2013) Revisiting the ethnographic turn in contemporary art, Critical Arts, 27:5, 459-473, DOI: 10.1080/02560046.2013.855513

Foster, H. (1995) The artist as ethnographer? In The traffic in culture. Refiguring art and anthropology, ed. G. Marcus and F. Myers, 302–309. Berkeley, LA and London: University of California Press